Building up the singing repertoire

How do the singer’s repertoire and the repertoire of the singing discipline develop according to time and context?

Introduction

Table des matières

Like the notion of instrumental or vocal technique, the repertoire stands out as one of the most important elements in the organisation of teaching in music schools. Both a support and an end in itself, it seems to offer the community of teachers and students an object of common culture around which musical practice and pedagogy are structured. In its disciplinary sense, the repertoire can be described as the corpus of works related to a particular instrument or group. For some disciplines – the piano in particular – this corpus seems too vast to be explored exhaustively by a single musician, while it sometimes seems too restricted to artists whose instrument has only slightly inspired composers to write solo pieces. In all cases, this repertoire actually has a selective dimension: a piece is said to ‘enter the repertoire’, i.e. it gains, at least temporarily, a recognition and notoriety that seems to ensure it a certain durability. It is then a question of the repertoire with a capital R, in other words the ‘great repertoire’. On the surface, this inclusion in the shelves of musical history is the result of a process of “decantation” by which works worthy of being preserved are separated from the others by the sole criterion of their intrinsic quality, thus becoming “classics”. In reality, the notion of the reception of works allows other criteria to emerge – such as access to concert programming or music publishing – which seem to be just as decisive in the survival of certain scores, and can explain their oblivion or justify their rediscovery.

The piano repertoire does not therefore constitute the whole of the pieces composed for this instrument throughout the history of music, but a selection of those – already plethoric[1] – that seem likely to endure. The case of singing offers a comparable horizon: its repertoire is obviously too vast to be embraced in a singer’s lifetime. Although some performers are admired for the large number of recordings or opera roles[2] they have sung in the course of their career, they will ultimately have covered only a small part of the singing repertoire.

Another meaning of the word – this time centred on the individual and not on the discipline – allows us to measure the exceptional nature of their contribution: as in the world of theatre, we can use the word “repertoire” to describe all the works that an artist has played and/or sung at a given moment in his or her theatrical or musical career. This definition applies to both professional and amateur practice. The repertoire of a particular singer is sometimes built on the fringe of the repertoire of his or her discipline, or only includes a very small segment of it[3] .

It could be said that the work of a singing teacher is situated at the meeting point of the two sets of terms used in the word repertoire: he or she must know both the repertoire of his or her discipline, the “great” repertoire, and constantly seek out the repertoire that will be most suitable for a particular singer. Knowledge of the singing repertoire cannot therefore be described as a static and circumscribed skill, but as a dynamic approach, renewed in the pedagogical process.

The aim of this course is therefore not to achieve an exhaustive knowledge of the singing repertoire (this would be an illusory objective), but to define a certain number of reference points in the wide panorama of the repertoire of the discipline, to open doors to lesser-known but pedagogically interesting works, and to identify tools for research and work. In its organization in lessons, the course uses a tree classification and sub-categories already used in the pedagogical milieu and established according to the common characteristics of the works considered: lyrical repertoire, oratorio, lied, melodies, vocal chamber music, contemporary music, ensembles. The second lesson is devoted to the bibliographic or digital tools that enable everyone to extend the scope of knowledge of the repertoire. The first lesson deals with the question of the constitution of the singing repertoire and the construction of the singer’s repertoire.

[1] The two-volume dictionary of piano music published in the Bouquins collection shows just how vast the repertoire of this instrument is. See Guy SACRE, La Musique de piano, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1998.

[2] Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau or Placido Domingo are examples.

[3] Some performers build their careers around one or two oratorio or opera roles: the Evangelist in Bach’s Passions, Pelléas in Debussy’s opera…

2. The repertoire of the singing discipline

2.1. History of the vocal repertoire

To say that the repertoire of a discipline can have a history, i.e. that it evolves from one period to another, may seem rather banal. In a linear vision, it is easy to consider that each period in the history of music sees the emergence of new great composers and brings its share of masterpieces that enrich the ever-growing catalogue of a discipline. Consultation of the archives, however, reveals that mechanisms other than a simple cumulative effect are involved in the constitution of repertoires: fashion, historical events, the social context and musicological studies contribute in particular to making and breaking the pantheon of great works of music in significant proportions. Thus, pieces that were widely taught at the Conservatoire at a certain time can completely disappear from its classrooms a few decades later and others, which had not been favoured by teachers for a long time, can be rediscovered and brought up to date.

The vocal repertoire in the concerts of the Paris Conservatoire between 1874 and 1900

The history of the singing repertoire could be the subject of a vast study. Without embarking on such a project, a study of the archives of the Paris Conservatoire allows us to measure the evolution of the pedagogical repertoire in France during the 19th centurye . In a book published in 1900 devoted to the institution, Pierre Constant[1] compiles the programme of concerts and student performances given once a year at the Conservatoire since 1800[2] . The vocal works performed, which are listed in Appendix I at the end ofee this course, reveal a repertoire that is sometimes unexpected for a 21st century reader: while the great composers of the 18th century, Mozart and Handel in particular, have a prominent place in the concert programmes, the selections of works written between 1760 and 1860 are sometimes surprising. Thus Luigi Cherubini is honoured with three lyrical works now forgotten by opera houses: Les Abencérages, Les Deux Journées and Anacréon. An opera by Gaspare Spontini entitled Fernand Cortez, which recounts Hernan Cortez’s conquest of the Aztec empire, appeared no less than six times in the programme between 1874 and 1900. Extracts from operas by Fromental Halévy – author of La Juive – are also sung on several occasions (Jaguarita l’indienne, Noé, Guido and Ginevra). Charles Gounod is represented by vocal works that are less appreciated today (Polyeucte, Ulysse and Mors et vita), but there is no trace of a programme of excerpts from operas that are widely known today, such as Faust or Romeo and Juliet. Daniel-Françoise Auber, Henri-Montan Berton and Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny complete the list of opera composers played in the students’ concerts, while the names of Saint-Saëns, Massenet, Bizet, Delibes and Offenbach – who seem to us to be indispensable in the French lyrical repertoire of the 19th century – do not appear on the programme. It is as much the presence of pieces now forgotten as the absence of great names from the repertoire that may surprise us: to note this fracture between the tastes of two eras is to admit that the criteria for constituting programmes have changed over the last hundred years. Is the regular presence of Cherubini’s arias justified by his responsibilities as director of the Paris Conservatoire between 1822 and 1842? Is the colonialist – and no doubt pro-Napoleonic – theme of Spontini’s Cortez no longer ‘politically correct’ for today’s audience? Is the scandal caused by the premiere of Bizet’s Carmen in 1875 enough to explain the absence of this composer from the Conservatoire’s concert programmes? Each of the questions raised by the reading of these archives finds an answer in the historical, social or aesthetic context of the periods considered.

2.2. Geography of the repertoire

In a globalised musical environment where the Internet provides efficient tools for publishing or following musical news, the dissemination of the works that make up the singing repertoire no longer seems to be limited by national borders. If, a few decades ago, one could speak of true national schools of singing – in the sense that the same musical works would not be taught in all parts of the world – the mobility of artists and musical supports today favours a progressive homogenisation of repertoires in the countries where Western art music is practised. However, there are still traditions linked to languages and cultures that offer pedagogues new areas to explore in terms of repertoire. Music for voice and piano is one of the areas where traces of such a ‘national identity’ can be detected. English melody, for example, is still an important element of tradition and culture in the UK, where specific courses are devoted to it in higher education. The Slavic and Nordic countries also perpetuate repertoires of melodies that are little sung outside their borders, largely due to a lack of knowledge of the languages set to music. While Dvořák is a very popular symphonic composer throughout the world, his melodies in Czech remain difficult to approach in terms of both meaning and pronunciation. The Cyrillic alphabet, on the other hand, tends to restrict Russian melodies to singers who can decipher it, limiting the dissemination of vocal works by such popular composers as Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff and Mussorgsky. In this case, the transmission of these repertoires, which have become elements of national culture, is based mainly on a phenomenon of patrimonialisation and identification of performers and the public with the works and the language set to music.

On the other hand, the dissemination and homogenisation of the repertoire at international level seems limited by the preference given to the original version in the performance of the works. eToday, one cannot imagine being able to sing a recital of Schubert’s lieder in their French translation in France, as was the norm in Paris in the 19th century. In a context where the return to the sources is becoming an aesthetic norm, performances of foreign operas in translated versions are often the exception in France, whereas this practice is more widely accepted in Anglo-Saxon countries[1] .

But the geography of the repertoire is also formed, to a lesser extent, at the regional level. There are thus disparities in the teaching and programming of vocal works within the national territory. The East of France is thus a land of choice for the German Baroque repertoire and Lieder, while the operetta of Marseille (in particular the works of Vincent Scotto) is only very rarely performed outside the Côte d’Azur.

To a certain extent, the study of the repertoire in music schools is therefore an opportunity for singers to become part of a regional or national tradition while at the same time acquiring the linguistic, stylistic and cultural tools to enable them to participate in an open and globalised musical world.

[1] The existence of opera houses such as the Deutsche Oper in Berlin or the English National Opera in London is a reminder of this age-old tradition.

[1] The existence of opera houses such as the Deutsche Oper in Berlin or the English National Opera in London is a reminder of this age-old tradition.

2.3. Reception of works and constitution of the repertoire

The short historical study sketched out on the basis of the concert programmes of the students of the Paris Conservatoire between 1874 and 1900 raises an essential problem for understanding the constitution of the vocal repertoire: how can we explain the fact that it can evolve from one period of history to the next to the point of leaving out works that were considered in other times to be indispensable? Is the intrinsic value of a musical work not enough to identify it as worthy of inclusion in the repertoire?

The theory of reception, founded in the 1970s[1] in the field of literature, sheds light on these questions and shifts the focus from the object – the work – to the community of those who take it up. According to this theory, a work cannot exist independently of the reception it receives from the various actors in the musical world: publishers, performers, the public, the press, etc. It is no longer a question of considering the value of a piece solely in terms of its supposed merit, but rather of understanding the extent of its dissemination, its success or failure, by taking into account all the phenomena of reception that structure the musical world. Since its composition, a musical work never ceases to evolve through the way it is listened to, commented on, interpreted and published over time. The same text is therefore constantly evolving as a result of the angle from which it is viewed, the emotional, historical or social context in which it emerges.

The reception of Bizet’s Carmen[2]

The phenomena of reception are famously illustrated in the musical field by the story of Carmen. As we know, this opera – which is today one of the most performed in the world – had a tumultuous beginning and Georges Bizet, who died three months after its creation, never saw its success. In 1875, the subject matter of the play seemed difficult to accept for an essentially bourgeois audience: Carmen, an independent, dangerous woman who defies the established moral order, is above all repulsive. The criticism is disastrous; in La Patrie, Achille de Lauzières castigates “the girl in the most revolting sense of the word; a girl mad about her body, giving herself up to the first soldier who comes along, on a whim, out of bravado, at random, blindly; […a bohemian, a savage, half-Egyptan or gypsy, half-Andalusian, […] in a word, the real prostitute of the bourbe and of the crossroads[3] “, while Le Siècle deplores: “The pathological state of this unfortunate woman, devoted, without truce or mercy […] to the ardours of the flesh, is fortunately a very rare case, more likely to inspire the solicitude of doctors than to interest honest spectators who have come to the Opéra-Comique with their wives and daughters[4] . ” The social context of the time was a determining factor in the reception of the work and greatly compromised its distribution.

But, more surprisingly, opposition to opera still exists, closer to home and in various forms. For example, the newspaper Le Monde[5] recalls the difficult reception of Carmen when it was first performed in China in the 1980s:

The moral scandal of 1875, however, outlived Carmen‘s triumph, as witnessed by its tribulations in China. When the work, at the request of the Beijing Central Opera, was premiered on 1er January 1982 in the Pont du Ciel hall, the reception was triumphant. But on 6 January, the French conductor Jean Périsson handed over the baton to the Chinese Zheng Xiaoying and the rest of the performances were compromised: the work, whose production had not been covered by the press, was suddenly judged to be “scabrous and subversive”[6] .

Even in Australia, the work was deprogrammed at the Perth Opera House in 2014 “so as not to offend a patron concerned with public health, whom a plot in a tobacco factory could offend[7] “. Contrary to what the worldwide success of the play might suggest, its reception is always linked to temporal and geographical disparities linked to the social, political or historical context. Its inclusion in the repertoire must be understood within the dynamic process of its reception by the actors of the music world.

Generally speaking, no musical work can be considered free of these reception phenomena; the constitution of the vocal repertoire responds to contexts and tastes that vary from a historical and geographical point of view. In addition to mastering the choices commonly made in the field of vocal works, knowledge of the repertoire also involves taking these mechanisms into account, which makes it possible to clarify the orientations taken by teachers and students in music schools throughout their training.

[1] Hans-Robert Jauß, Literaturgeschichte als Provokation der Literaturwissenschaft, Frankfurt am Main 1970, p. 189.

[2] http://mobile.lemonde.fr/m-actu/article/2016/08/09/carmen-objet-de-tous-les-scandales_4980186_4497186.html?xtref=

[3] Achille de Lauzières, ‘Revue musicale’, in La Patrie, 8 March 1875.

[4] Oscar Comettant, “Revue musicale”, in Le Siècle, Paris, 8 March 1875, p. 2.

[5] Philippe-Jean Catinchi, “Carmen, objet de tous les scandales”, in Le Monde, 9 August 2016, available online: www.lemonde.fr/m-actu/article/2016/08/09/carmen-objet-de-tous-les-scandales_4980186_4497185.html

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

2.4. The role of publishing and programming in building the repertoire

While the reception by the public and the critics have long been part of the daily life of composers and performers, the role of programmers and publishers is sometimes more difficult to grasp. Yet these actors in the musical world are among the most important in the dissemination of works from their composition and at every stage of their presentation to the public. First of all, it is crucial for a musician to be able to have his or her works published, preferably by a solid and recognised publishing house, so as to make them accessible to as many people as possible. Ideally, the piece is engraved, printed and then distributed through the network of musical score distributors. Then, it must be created, accepted by concert organisers and remain on the bill. The promotion of musical works is therefore a very important element in a composer’s career. For the luckiest composers, an institutional commission allows them to do most of this work: a contemporary opera intended to be premiered in a lyric theatre thus benefits from all of the theatre’s communication and dissemination apparatus (posters, programmes, press coverage, possible co-production, etc.). In most cases, composers have to fight to have their works performed in concert and gain a certain amount of media recognition. The inclusion of a musical work in the repertoire depends in part on the process of its reception by publishers and concert programmers.

Example of the rediscovery of a vocal repertoire: the melodies of Charles Bordes, a composer of the Belle Époque

In recent decades, the widespread use of computer tools and access to the Internet has made the dissemination of musical works more flexible; alternative channels of promotion have been created, which composers of past centuries could not avail themselves of. Musicological studies provide us with detailed information on the importance of reception phenomena in the dissemination of works, and consequently on the mechanisms of their inclusion in the repertoire. The example of Charles Bordes is quite emblematic of the problems of promotion that composers had to solve at the end of the 19th centurye . His work as a composer, long forgotten, has recently been rehabilitated, notably through a recording of pieces for solo piano and the complete works of his melodies, published by Timpani[1] .

Born in 1863, Bordes belonged to the close circle of César Franck’s pupils. Without ever having attended the Conservatoire, he led a rather atypical musical career marked by the foundation, in 1890, of the Chanteurs de Saint-Gervais, a vocal ensemble with which he devoted himself to the rediscovery of the vocal repertoire of the Renaissance and French Baroque music. Founder of the Schola Cantorum alongside Vincent d’Indy and Alexandre Guilmant, he advocated a more complete training for musicians, less focused on instrumental virtuosity. Like many young musicians of the time, he encountered difficulties in getting his compositions published and had to appeal to the generosity of those close to him – in particular Ernest Chausson[2] – to have his first songs published by Hamelle, partly on a self-publishing basis. Permanently unable to publish an ever-increasing body of melodies, he founded in 1902 a collaborative enterprise called Édition mutuelle, through which he offered composers close to the Schola a structure capable of ensuring the engraving and distribution of their compositions. The Édition mutuelle operated on a system of subscriptions and on financial solidarity between the musicians who used its services. Many young composers thus found a partial solution to the problems encountered in promoting their works. Bordes himself benefited greatly from the advantages offered by the Édition mutuelle: more than half of the corpus of his melodies[3] was published there, becoming rapidly available to performers. In a series of articles devoted to French Lieder composers, Georges Servières underlines the importance of this publication in the reception of Bordes’ songs, which he ranks among those of the most famous French composers:

A place had long been reserved for Charles Bordes in this series of French Lieder, in which I have successively studied the vocal works of Fauré, Duparc, Chausson and Debussy. Unfortunately, at the time I undertook this work, hardly any of Bordes’s songs – among the oldest – had been engraved, and he himself, with his characteristic carelessness for personal success, was much more concerned with spreading knowledge of the great polyphonic works of the sixteenth centurye or the religious cantatas of J. S. Bach than with publishing his productions and forcing the resistance of publishers. While the most mediocre Prix de Rome winner is welcomed by them from the outset, for one or more songbooks, Bordes was obliged to resort to the system of mutual publishing, that is to say, to publish himself at his own expense, even though he has been famous for ten years and has nearly forty[4] .

In the field of programming, Bordes relied on the Société nationale de musique and the numerous concerts he organised in Paris and in the provinces with the Chanteurs de Saint-Gervais to have his works heard. Some of his melodies met with great success with the public, and the press reported on these successes. Throughout his life, the promotion of Bordes’ works was closely linked to his activities as choirmaster and head of the Schola Cantorum, so much so that when he died prematurely in 1909, it was the composer, the musicologist, the pedagogue and the leader of French musical life who was unanimously acclaimed.

After his death, his cellist brother Lucien Bordes temporarily took over the promotion of his work before one of his close friends, Pierre de Bréville, edited the melodies in two collections published by Rouart-Lerolle in 1914[5] and then by Hamelle in 1921[6] . This important work temporarily ensured the dissemination of the pieces but, in the absence of direct descendants of the composer, interest in them diminished and, after a few decades, they seemed to have almost fallen into oblivion. With no new editions of the melodic corpus since the 1920s, it is perhaps the existence of a commemorative monument inaugurated in June 1923 on the church square of his native village that has led to a renewed interest in Charles Bordes. A local association was set up with the mission of organising an annual musical and scientific gathering dedicated to the composer. It is thanks to its members that the pieces are reprogrammed in concert and that the recordings published by Timpani can be released.

The oblivion and subsequent rediscovery of Bordes’ musical work is not an isolated example. More famous figures in the history of music have suffered a similar fate[7] and the interest of the public, the media and society in a musical work is not a linear process. Many pieces disappear from the repertoire and are sometimes reinstated by chance or by the contribution of certain players in the musical world. The work carried out by the Bru-Zane Foundation for the promotion of the French music repertoire of the 19th centurye is part of this problem: it is largely thanks to the financial and logistical support of this institution that composers such as Théodore Dubois can be rediscovered, or that operas as rare as Édouard Lalo’s La Jacquerie can make their return to the opera stage[8] .

These examples show that the constitution of the singing repertoire is intimately linked to the musical, institutional and editorial practices of each period, and this since their creation.

[1] Charles BORDES, Mélodies, works for piano, Sophie Marin-Degor, Jean-Sébastien Bou, François-René Duchâble, Timpani, 2012 and Charles BORDES, Mélodies vol. 2, Sophie-Marin Degor, Géraldine Chauvet, Éric Huchet, Nicolas Cavalier, François René Duchâble, Timpani, 2013.

[2] Jean-François ROUCHON, Les Mélodies de Charles Bordes, histoire et analyse (1883-1909), thesis prepared at the University of Lyon-Saint-Étienne, 2016, p. 82.

[3] Ibid. , p. 87.

[4] Georges Servières, “Lieder Français”, in Le Guide musical, Brussels, XLIX, no 17 (26 April 1903), p. 370.

[5] Charles Bordes, Dix-neuf œuvres vocales, Paris, Rouart-Lerolle et Cie, 1914.

[6] Charles Bordes, Quatorze mélodies, Paris, Hamelle, 1921.

[7] We could multiply the examples, Mozart, Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn…

[8] This opera composed in 1895 was programmed at the Festival de Radio-France in Montpellier in July 2015.

3. The singer's repertoire

Although in music schools the notion of repertoire most often refers to a disciplinary field, it can, in another sense, be linked to the performer himself. In practice, a singer’s repertoire is quite different from that of his or her discipline: the range and typology of voices means that a vocal piece will very rarely be suitable for all the singers in a class. Each of them will have to identify the vocal works intended for them and progressively develop their skills to be able to perform them. The singer’s repertoire is the set of pieces that he or she can already perform, but also, in a broader sense, those that are likely to correspond to his or her vocal and artistic abilities in the long run.

Guiding students in the discovery and construction of their repertoire is one of the daily tasks of a singing teacher. To do this, the teacher relies on his or her own experience and culture of the repertoire of the discipline. More often than not, they tacitly refer to an aesthetic tradition which tends to reserve a particular work for a certain type of voice. It seems obvious that the same student cannot sing the arias of Sarastro and Tamino in Mozart’s Magic Flute at the same time. The coherence of a singer’s repertoire places him or her within a vocal category (counter-tenor, tenor, baritone or bass for men) which the teacher’s expertise makes it possible to determine from the outset or gradually. But the characterisation of the repertoire also takes place within each of these vocal categories: a soprano cannot tackle all the arias in the repertoire which are collected in a collection of arias for soprano. The definition of vocal sub-categories is again part of a tradition often inherited from the world of opera, and the boundaries defined between the sub-categories, which are sometimes tenuous, depend largely on the historical or geographical context in which one is situated. The repertoire of a French ‘lyric baritone’ does not correspond to that of the German ‘lyrischer Bariton’, and the very notion of ‘Kavalierbariton’ is often only used in the German-speaking world. Similarly, the consistency of opera role casting also varies significantly across the ages. One only has to listen to the recordings of the great opera singers of the early 20th centurye to be convinced of this.

3.1. Criteria for selecting a singer's repertoire

The objective criteria for defining a singer’s repertoire are most often difficult to explain. In some cases, reference to important figures in the world of opera can help to find reference points, but the French-language literature is singularly lacking in tools for dealing with this question. In an article published in 2002[1] , John Nix attempts to define a certain number of criteria that can guide the teacher in the choice of a student’s repertoire and tries to answer the question: “How can the repertoire be systematically chosen to best suit the needs of each student?[2] “

Nix responds by defining four main categories of criteria that should be used in repertoire selection – “the singer’s physical limitations, the singer’s vocal classification, emotional/expressive factors and musical skills[3] ” and states: “Depending on the type of student – beginner, intermediate, advanced – these criteria take on different levels of importance. For beginners, physical limitations and vocal classification are predominant; for intermediate, advanced and professional levels, emotional factors and musical skills become equally important[4] .

In the rest of the article, the author proposes an analysis of each of the criteria which can be summarised in the following table:

Category | Criterion | Indexes |

Physical limitations | Age of the singer | Physical maturity required to tackle a given piece |

Duration of previous vocal training | Training of muscles, existence of technical elements installed or not | |

Individual technical problems | ||

Emotional factors | Emotional maturity | Limits for approaching a given piece |

Temperament or personality of the singer | Reactivity, intellectuality, spirituality, impulsiveness | |

Preferences for musical or poetic styles | ||

Musical skills | Shades | |

Melodic, harmonic or rhythmic difficulties | ||

Language, pronunciation | ||

Voice classification | Ambitus | |

Tessitura dell'aria | ||

Melodic distribution in relation to the singer's passage zones | ||

Nature of the vowels to be sung on the extreme notes |

Although Nix’s article does not aim to solve all the problems of choosing a pedagogical repertoire, it does offer a grid for reading and analysing a singer’s skills at a given moment and the demands made of a vocal work. It should be pointed out that Nix is concerned here with the choice of pieces intended for a concert or an examination. Some would say that it may be useful, in certain circumstances, to offer the student a piece that is judged a little too difficult to master at the moment, but which will be a greater source of motivation for him or her, a good learning ground outside of any public performance objective.

3.2. Tessitura definition tools

Among the criteria defined by John Nix, the singing teacher community will undoubtedly consider vocal classification as one of the most decisive in the choice of repertoire. The match between a student’s skills and the demands of a vocal work is one of the main issues in this choice. However, precise and effective tools available to teachers are rare and the selection of repertoire is often made according to criteria mainly linked to culture and tradition. There is little documentation on the range of solo vocal works, and even less detailed commentary on the skills needed to sing a particular piece.

In an article published in 2008, Ingo Titze[1] attempts to propose a method for quantifying tessitura. At first sight a bit technical, his work allows to model the notion of tessitura and aims at obtaining a graphical representation that summarizes the vocal characteristics of the pieces of the repertoire. The author defines two main data to quantify the tessitura: the temporal dose (tp ), or accumulated duration of vocal emission on a given pitch during the whole piece, and the cyclic dose, product of the temporal dose and the fundamental frequency of the sung note (Fp ).

- Temporal dose = tp

- Cyclic dose = Fp . tp

The temporal dose can be measured in seconds or note duration, while the cyclic dose is quantified as the number of cycles of vocal cord vibrations on a given note.

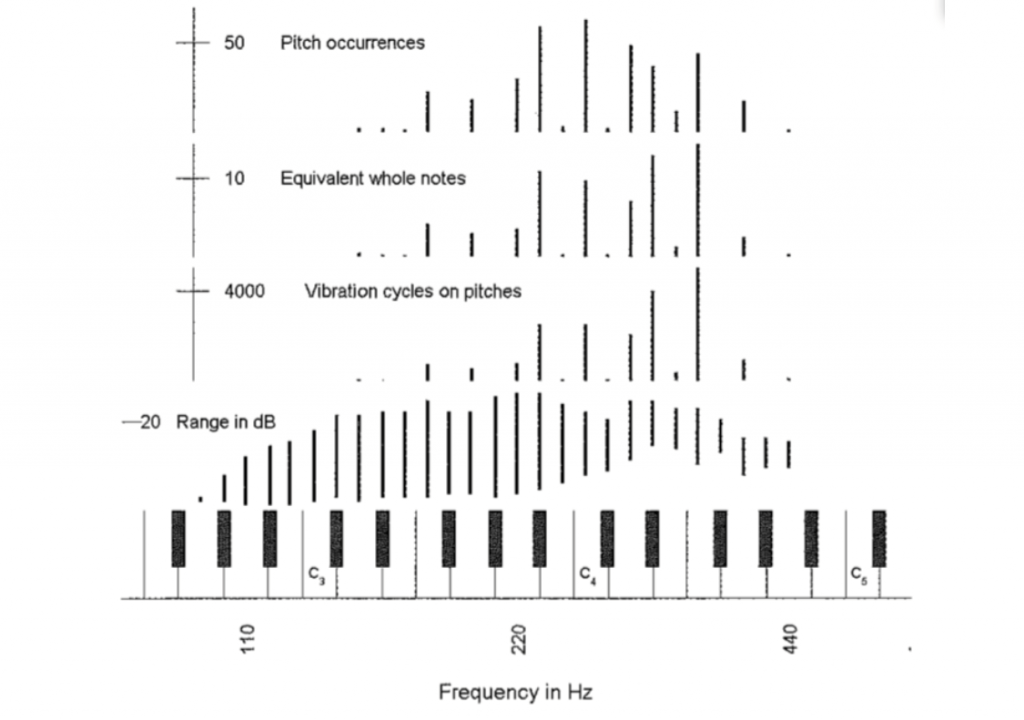

If the cyclic dose refers to a notion that may seem more complex to exploit, the measurement of the temporal dose makes it possible to answer a simple question: how long will a singer emit each of the notes written on the score throughout the piece? The graphical representation provides an ‘X-ray’ of the piece, and a better understanding of the distribution of pitches and vocal difficulties it contains. Titze analyses in particular the aria of Don Ottavio in act 2 of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, from which he derives the following diagram (“tessituragram”):

[1] Ingo TITZE, “Quantifying tessitura in a song”, in Journal of singing, Sept. 2008, 65.1, p. 59-60.

From top to bottom, the figure represents the number of occurrences for each pitch, the temporal dose (total duration) in note duration equivalents and then the number of vibratory cycles, all related to a horizontal frequency scale of sounds whose values are plotted on a piano keyboard. Just above this scale is added the sound volume measured during the recording of the tune performed by a singer.

The exploitation of the results allows the author to bring out the characteristics of the air (occurrences, cumulative duration and number of vibratory cycles for each pitch), all of which are precise data that will allow the teacher to orientate his choices of repertoire for a given student.

The results of the study suggest several comments. First of all, although the tessituragram represents a real advance in the precise knowledge and understanding of the characteristics of a vocal piece, it may seem insufficient to describe all its difficulties. For example, it says nothing about the length of musical phrases, the nature of the intervals that compose them, or the time left for the singer to breathe. This information could be given by a representation of the “profile” of the piece. The tessitura is therefore a necessary but not necessarily sufficient element to describe a piece of repertoire. Secondly, such a study can only be truly used to specify a singer’s repertoire in a comparative approach that assumes the existence of a significant number of these ‘tessituragrams’. It is in the detailed confrontation of the data of different arias of the repertoire that it would be possible to better understand their characteristics. Finally, a complete exploitation of the data could leave room for a reversal of focus: the analysis of the diagram suggests attributing the aria to a certain singer profile; conversely, the analysis of the repertoire of a confirmed singer could allow the emergence of criteria common to the arias he or she interprets and thus to define new methods of exploitation of the data.

Ingo Titze’s work could therefore be the embryo of a much larger research project, the aim of which would be to enrich the literature on the repertoire.

Conclusion

The term ‘repertoire’ refers to several different concepts that teachers and students in music schools are confronted with. The ‘great repertoire’ is different from the repertoire of the discipline, but also from the pedagogical repertoire and the singer’s repertoire. Far from constituting an immutable and stable entity according to time and place, the singing repertoire undergoes permanent variations and modifications linked to factors as diverse as the historical, aesthetic, political, social, linguistic or cultural context. The reception of works thus plays a determining role in its constitution.

Knowledge of the singing repertoire requires both mastery of the discipline’s repertoire and ongoing research into the construction of the student’s repertoire. This research dimension is one of the central elements of the teaching activity. For the time being, there are few tools for a precise description of the singing repertoire in French-language literature; however, work carried out in various countries is gradually leading to a better knowledge of vocal works. It is undoubtedly at the level of the teaching community and in a collaborative work approach that these elements of professional culture can be shared and enriched.

Annex I

Vocal programme of the Paris Conservatoire concerts between 1874 (date of their reintroduction) and 1900

1874 : SPONTINI, Fernand Cortez, aria; MOZART, Ave verum; SPONTINI, Fernand Cortez, aria; ROSSINI, Messe solennelle, Gloria; CHERUBINI, Les Abencérages, aria

1875: GLÜCK, Armide, Air and chorus; WEBER, Obéron, Act 1 Finale (Air, duet and final chorus); MOZART, The Marriage of Figaro, Air; ROSSINI, The Siege of Corinth, solo and chorus

1876 : GOUNOD, Sappho, Stances, MOZART, The Magic Flute, march and aria; SPONTINI, Fernand Cortez, scene of the revolt; MÉHUL, Joseph, aria; GLUCK, Armide, chorus and solo; HAENDEL, The Messiah, Alleluia

1877: MOZART, The Abduction from the Seraglio, aria; RAMEAU, Les Fêtes d’Héré, chorus and duet; MÉHUL, Stratonice, aria; ROSSINI, Messe solennelle, Agnus dei; ROSSINI, Moïse, Act III finale.

1878: AUBER, L’Enfant prodigue, aria; CHERUBINI, Les Deux Journées, chorus and solo; HALÉVY, Jaguarita, Act I finale; RAMEAU, Hippolyte et Aricie, chorus; BERLIOZ, Marche des pèlerins, solo viola; BERTON, Montano et Stéphanie, aria; HALÉVY, Prière de Noé, solo; AUBER, Fo-Li-Fo, chorus

1879: MOZART, Cosi fan tutte, aria; HAYDN, The Seasons, aria and chorus; MOZART, The Marriage of Figaro, aria; ROSSINI, Count Ory, solo and quartet.

1880 : HAENDEL, Julius Caesar, aria; ROSSINI, Messe solennelle, Sanctus; WEBER, Obéron, Barcarolle, aria and chorus; VERDI, Un ballo in maschera, cavatina; SPONTINI, Fernand Cortez, duet; HAENDEL, Le Messie, chorus, recitative and Alleluia

1881: MOZART, The Magic Flute, aria; GLUCK, Iphigénie en Tauride, fragment from Act II; AUBER, The Bride of the King of Garbe, chorus; SPONTINI, Fernand Cortez, scene of the revolt; MOZART, The Marriage of Figaro, aria; ROSSINI, The Siege of Corinth, Act II finale.

1883: GLUCK, Iphigénie en Aulide, Overture, scene and aria, chorus and scene, chorus, scene and aria, recitals, chorus, aria, recitals and aria with chorus, recitals and duet, aria, recitals, quartet and chorus, NICOLO, Joconde, Romance; SPONTINI, Fernand Cortez, duet; AUBER, Le Concert à la cour, aria; ROSSINI, Guillaume Tell, act I chorus.

1884: MENDELSSOHN, Elijah in full

1885 : HAYDN, The Creation of the World, 1ère part ; HALÉVY, Guido and Ginevra, aria ; HAYDN, The Creation of the World, fragments of 2e and 3e parts.

1887: WEBER, Euryanthe, aria; ROSSINI, Messe solennelle, Gloria; MONSIGNY, La Belle Arsène; HAENDEL, Le Messie, chorus, pastorale and alleluia.

1888: MOZART, Requiem, excerpts; CHERUBINI, Anacreon, aria; GRÉTRY, Zémire et Azor, aria; MOZART, The Marriage of Figaro, aria; ROSSINI, The Siege of Corinth, scene and chorus from Act III

1897 : MENDELSSOHN, Tu es Petrus, choir ; BACH, Cantate pour la fête de Pâques (n°4), Versus I to VII ; M. HAYDN, Tenebræ factæ sunt, choir ; LOTTI, Crucifixus, choir ; HAENDEL, Ode à Sainte Cécile, Marche, aria, recitative and chorus with solo.

1898 : LULLY, Armide, chorus and solo ; RAMEAU, Dardanus, trio and chorus ; BRAHMS, Requiem, n° 1 and 6 ; SCHUMANN, Les Adieux des montagnards, soli ; GOUNOD, Ulysse, chorus of the naiads, chorus of the pigs, solo scene and chorus.

1899: RAMEAU, Quam dilecta, aria, chorus, aria, trio, aria and chorus, aria, chorus; JANEQUIN, La Bataille de Marignan, chorus; GOUNOD, Polyeucte, act II, 2nd tableau.

1900: BACH, Cantate pour tous les temps, fragments; LOTTI, Crucifixus, chorus; SCHUMANN, Ferme tes yeux; GLUCK, Iphigénie en Aulide, fragments from Act I; GOUNOD, Mors et vita, Judex.